Solidity: Storage Slots of Primary Types

Overview

Variables in a smart contract store their value in two primary locations:

- bytecode: Immutable variables

- storage: Mutable variables

Bytecode

Bytecode is the part of a smart contract that never changes once the contract is deployed. It stores all the unchangeable information, including:

- Fixed Values: Any constant or immutable variables you set become part of the bytecode.

- Program Code: The actual instructions for your contract, including hardcoded numbers (like

uint256 x = 20in a function), are stored here.

In essence, bytecode is like the permanent blueprint of your contract that lives on the blockchain and shows everything that cannot be altered.

contract ImmutableVariables {

uint256 constant myConstant = 100;

uint256 immutable myImmutable;

constructor(uint256 _myImmutable) {

myImmutable = _myImmutable;

}

function doubleX() public pure returns (uint256) {

uint256 x = 20;

return x * 2;

}

}

Storage

Storage is where a smart contract permanently keeps its changeable data, like balances or counters.

- These storage variables live on the blockchain and keep their values until a transaction updates them.

- They are stored in fixed-size spaces called storage slots (each 32 bytes in size), assigned by Solidity based on the order of declaration.

- Storage variables are variables that are declared within the global scope of a contract (except for immutable and constant variables).

contract StorageVariables{

uint256 x;

address owner;

mapping(address => uint256) balance;

// and more...

}Storage Slots

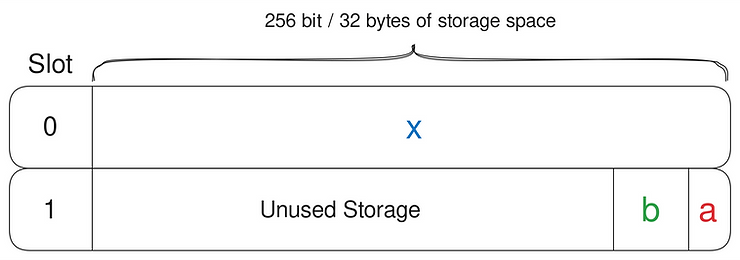

A smart contract's storage is organized into storage slots.

- Each slot has a fixed storage capacity of

256 bitsor32 bytes. - Storage slots are indexed from

0to2^256 - 1. - The Solidity compiler gives each storage variable its own slot in the order you declare them. This means the first variable gets the first slot, the second gets the next, and so on, making the storage predictable and fixed.

contract StorageVariables {

uint256 public x; // first declared storage variable

uint256 public y; // second declared storage variable

}

- When queried,

xandywill consistently read from the values stored in their respective storage slots. - A variable cannot change its storage slot once the contract is deployed to the blockchain.

- If the value of

xandyis not initialized, it defaults to zero. All storage variables default to zero until they are explicitly set.

contract StorageVariables {

uint256 public x; // Uninitialized storage variable

function return_uninitialized_X() public view returns (uint256) {

return x; // returns 0

}

}To set the value of x to 20, we can call the function set_x(20).

function set_x(uint256 value) external {

x = value;

}This transaction triggers a state change in slot 0, updating its state from 0 to 20.

Inside Storage Slots: 256-bit Data

Individual storage slots store data in 256-bit format

The default value of slot 0 is 0. After calling set_x(20), slot 0's state was changed to the bit representation of uint256 20.

Storage Packing

So far, we've conveniently dealt with uint256 variables, which span the entire 32 bytes of a storage slot. Other primitive data types, such as uint8, uint32, uint128, address, and bool, are smaller in size and uses less storage space. They can be packed together within the same storage slot.

The table below illustrates the storage size of some primitive data types.

| Type | Size |

|---|---|

bool | 1 byte |

uint8 | 1 byte |

uint32 | 4 bytes |

uint128 | 16 bytes |

address | 20 bytes |

uint256 | 32 bytes |

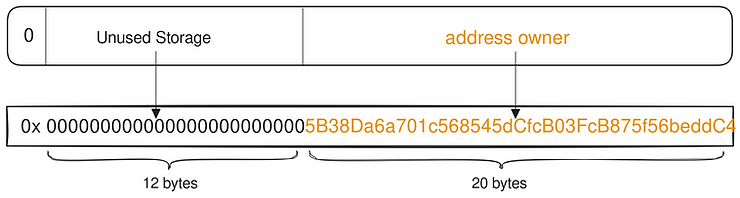

For example, a storage variable of type address will require 20 bytes of storage space to store its value, as illustrated in the table above.

contract AddressVariable{

address owner = 0x5B38Da6a701c568545dCfcB03FcB875f56beddC4;

}In the contract above, owner will use up 20 bytes of the 32 bytes available to store its value.

When declared in sequence, smaller sized variables live in the same storage slot if their total size is less than 256 bits or 32 bytes.

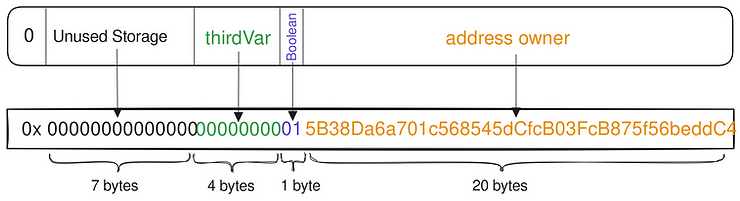

Say we declared a second and a third storage variable of type bool (1 byte) and uint32 (4 bytes), their values will be stored within the same storage slot as owner, slot 0, at the unused storage space.

contract AddressVariable {

address owner = 0x5B38Da6a701c568545dCfcB03FcB875f56beddC4;

bool Boolean = true;

uint32 thirdVar = 5_000_000;

}The Boolean variable is stored in the first available byte to the left of the owner's data, filling the least significant unused space. Remember, Solidity arranges packed variables from right to left.

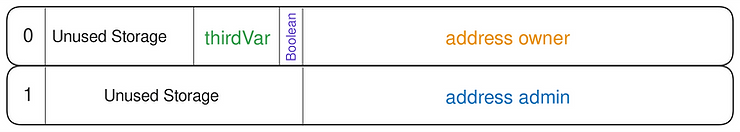

If we were to introduce a fourth storage variable, address admin, its value will be stored in the next storage slot, slot 1.

contract AddressVariable {

address owner = 0x5B38Da6a701c568545dCfcB03FcB875f56beddC4;

bool Boolean = true;

uint32 thirdVar = 5_000_000;

address admin = 0xAb8483F64d9C6d1EcF9b849Ae677dD3315835cb2;

}Admin's value needs 20 bytes, but slot 0 only has 7 bytes left. Since it can't be split across slots, Solidity stores it entirely in slot 1 instead.

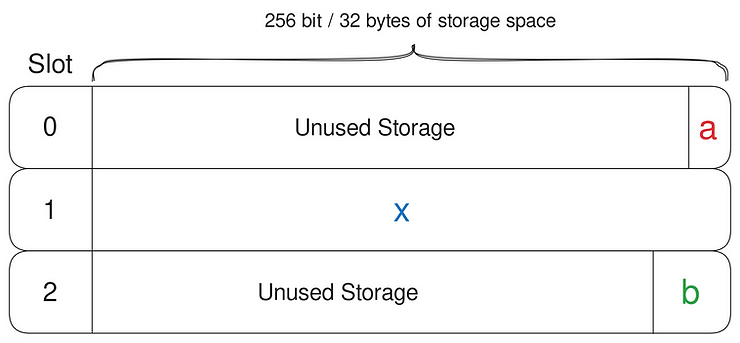

Best Practice: Declare Smaller Variables Together

uint16 public a;

uint256 public x; // uint256 in the middle

uint32 public b;In this arrangement, uint16 a and uint32 b will not be packed together.

A better practice is to reorder the declarations to allow the smaller datatypes to be packed together.

uint256 public x;

// packed together

uint16 public a;

uint32 public b;This configuration allows a and b to share a storage slot, thereby optimizing storage space.

Yul Assembly for Storage Operations

Yul allows direct access to storage slots, giving more control over reading and writing data.

sload(slot)→ Reads the value stored in a specific slot.sstore(slot, value)→ Updates a slot with a new value..slot→ Returns the storage location of a variable..offset→ Gives the byte offset within a slot.

This flexibility helps optimize smart contract storage and gas usage.

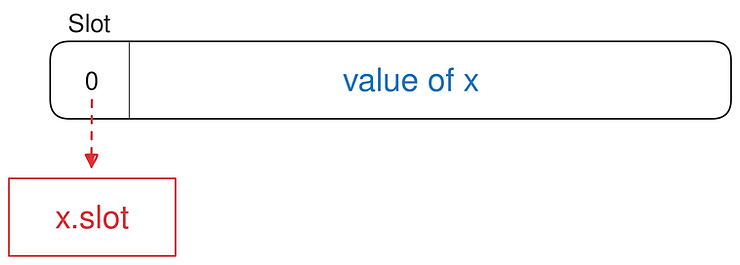

The .slot Keyword

The contract below contains three uint256 storage variables.

contract StorageManipulation {

uint256 x;

uint256 y;

uint256 z;

}You should be able to deduce that x, y and z store their values in slot 0, slot 1 and slot 2, respectively. We can prove this by accessing the storage variable’s property using the .slot keyword.

.slot tells us at which storage slot a variable keeps its value.

function getSlotX() external pure returns (uint256 slot) {

assembly {

slot := x.slot // returns slot location of x = 0

}

}

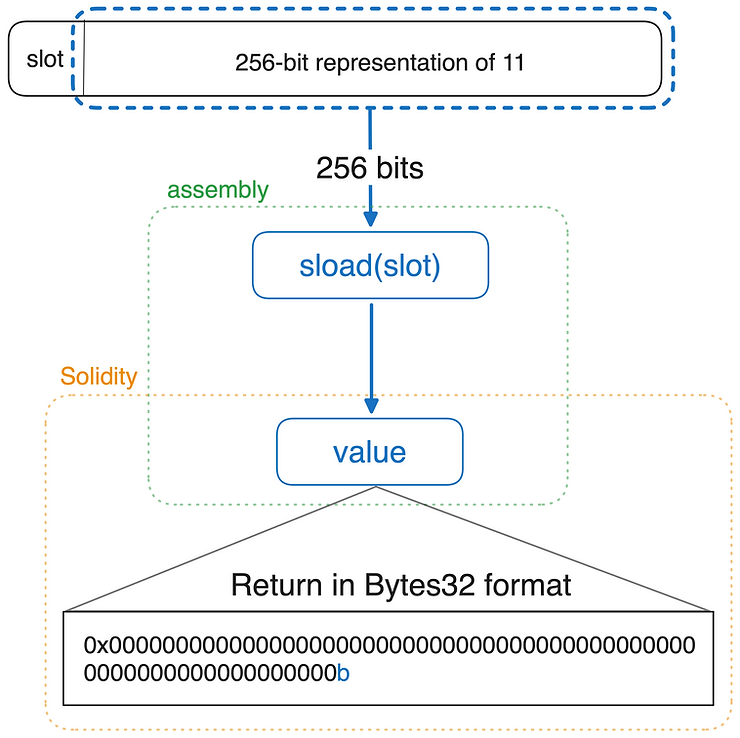

sload()

Yul allows us to read the value stored by individual storage slots. The sload(slot) opcode is used for this purpose.

It requires one input, slot, the storage slot identifier and returns the entire 256 bit of data stored at the specified slot location.

The slot identifier can be either the .slot keyword (sload(x.slot)), a local variable (sload(localvar)) or a hardcoded number (sload(1)).

contract ReadStorage {

uint256 public x = 11;

uint256 public y = 22;

uint256 public z = 33;

}The function readSlotX() retrieves the 256 bit data stored in x.slot (slot 0) and returns it in uint256 format, which equals 11.

function readSlotX() external view returns (uint256 value) {

assembly {

value := sload(x.slot)

}

}sload(0)reads from slot 0, which stores the value of 11.sload(1)reads from slot 1, which stores the value of 22.sload(2)reads from slot 2, which stores the value of 33.sload(3)reads from slot 3, which stores nothing, it is still in its default state.

The function sloadOpcode(slotNumber) allows us to read the value of any arbitrary storage slot. It then returns the value in uint256 format.

function sloadOpcode(uint256 slotNumber)

external

view

returns (uint256 value)

{

assembly {

value := sload(slotNumber)

}

}sload() does not perform a type check.

In Solidity, we cannot return a uint256 variable in bool format as it will incur a type error.

function returnX() public view returns (bool ret) {

ret = x; // type error

}But if the same set of operation is performed in Yul, the code will still compile.

function readSlotX_bool() external view returns(bool value) {

// return in bool

assembly{

value:= sload(x.slot) // will compile

}

}In assembly, all variables are treated as bytes32, meaning they take up 32 bytes of space. However, outside of assembly, they return to their original type and format.

Because of this, we can inspect a storage slot's value in bytes32 format, allowing us to see its raw data representation before Solidity applies type-specific formatting.

contract ReadSlotsRaw {

uint256 public x = 20;

function readSlotX_bool() external view returns (bytes32 value) {

assembly {

value := sload(x.slot) // will compile

}

}

}

sstore()

Yul gives us direct access to modify the value of a storage slot using the sstore() opcode.

sstore(slot, value) stores a 32-byte long value directly to a storage slot.

slot: This is the targeted storage slot which we are writing to.value: The 32-byte value to be stored at the specified storage slot. If the value is less than 32 bytes, it will be left padded with zeroes

sstore(slot, value) overwrites the entire storage slot with a new value.

contract WriteStorage {

uint256 public x = 11;

uint256 public y = 22;

address public owner;

constructor(address _owner) {

owner = _owner;

}

function sstore_x(uint256 _val) public {

assembly {

sstore(x.slot, _val)

}

}

function set_x(uint256 _val) public {

x = _val;

}

}sstore_x(_val) directly updates the value stored in the storage slot that x references, effectively changing the value of x.

Both sstore_x(_val) and set_x() perform the same function: They update the value of x with a new value.

sstore() also does not type check.

Normally, when we try to assign an address type to a uint256 type, it would return a type error and the contract would not compile:

address public owner;

function TypeError(uint256 value) external {

owner = value; // ERROR: Type uint256 is not implicitly convertible to expected type address.

}This error will not trigger with sstore() as it does not perform a type check.

contract WriteStorage {

address public owner;

function sstoreOpcode(uint256 value) public {

assembly {

sstore(owner.slot, value)

}

}

}Reference

- RareSkills where I copied the diagrams from.

Related Posts

Find more posts like this one.

January 10, 2024

I'm Done Typing npm

Are you tired of typing npm?

Read more

May 29, 2025

Load balancer RPC endpoints

Did your Dapp cash because of RPC endpoint?

Read more

May 15, 2025

Solidity: Storage Slots of Complex Types

This article explains how Solidity stores smart contract data using storage slots, packing for efficiency, and Yul assembly for direct storage access

Read more

May 13, 2025

Cache Strategies

Cache strategies are a way to improve the performance of a system.

Read more

May 9, 2025

Load Balancer

A load balancer is a device that distributes network traffic between multiple servers

Read more

May 9, 2025

Rate Limiting

Rate limiting is a technique used to control the rate of requests to a service.

Read more

May 13, 2025

Redis

Redis is an open-source, in-memory data structure store used as a database, cache, and message broker.

Read more

May 19, 2025

Javascript: deep cloning object methods

Read more

May 7, 2025

Prettier merged type

Prettier merged type

Read more

January 5, 2025

Should we use type or interface in typescript

Read more